Nearly 60% of long-term care nurse leaders have seriously considered quitting their jobs in the last three months, a nearly 10-point jump versus 2021, according to the fourth annual McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey.

That was trailed slightly by administrators at 52%, further proof that the turnover threat at the highest in-building levels is all too real. The 2022 findings come as regulators are putting more emphasis on staffing consistency.

The survey drew nearly 750 responses from directors of nursing, assistant directors of nursing and administrators, who sent mixed signals about job satisfaction and their willingness to remain in leadership positions at the nursing home level.

Data was collected through email solicitations over a two-week period in July and August.

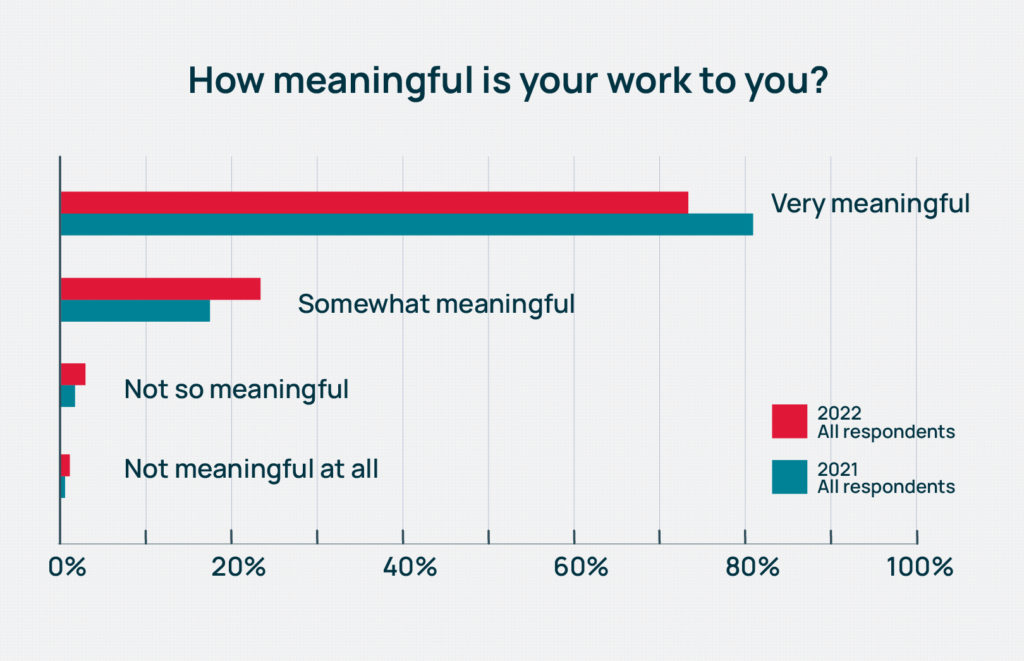

Among the most positive aspects of the survey remains the meaningful nature of the work. This year, 73% of respondents said they found their work “very meaningful.” It’s still, however, a significant slide from 81% just last year.

“DONs and administrators really like what they do. They really do love serving the residents, running the building and the mission of what they do. They don’t want to quit,” Cara Silletto, president and chief retention officer at HR consulting firm Magnet Culture, told McKnight’s. “But what I’m picking up on is that organizations continue to push these leaders beyond their limits and beyond what is sustainable long-term. That is a huge wake-up call that these organizations need to realize.”

Those thoughts were echoed by geriatrician and Regenstrief Institute researcher Kathleen Unroe, MD. She recently authored a Journal of the American Geriatrics Society editorial noting the negative effects of turnover at the administrator level. It creates a void that may be disruptive, prompt other staff to leave, and require process reorganization under a new leader, she wrote.

“The administrative team, their leadership sets the tone, creates the culture,” she told McKnight’s in August. “Their level of experience, their investment in the building is so evident when it is present. You can have all kinds of innovative, quality type programs under way, and when you have turnover in the clinical and administrative leadership, they have different priorities.”

Too much sacrifice?

Consistency may be a key goal for nursing homes, but this year’s survey indicates skilled nursing hasn’t staunched the kinds of wounds that lead workers to quit.

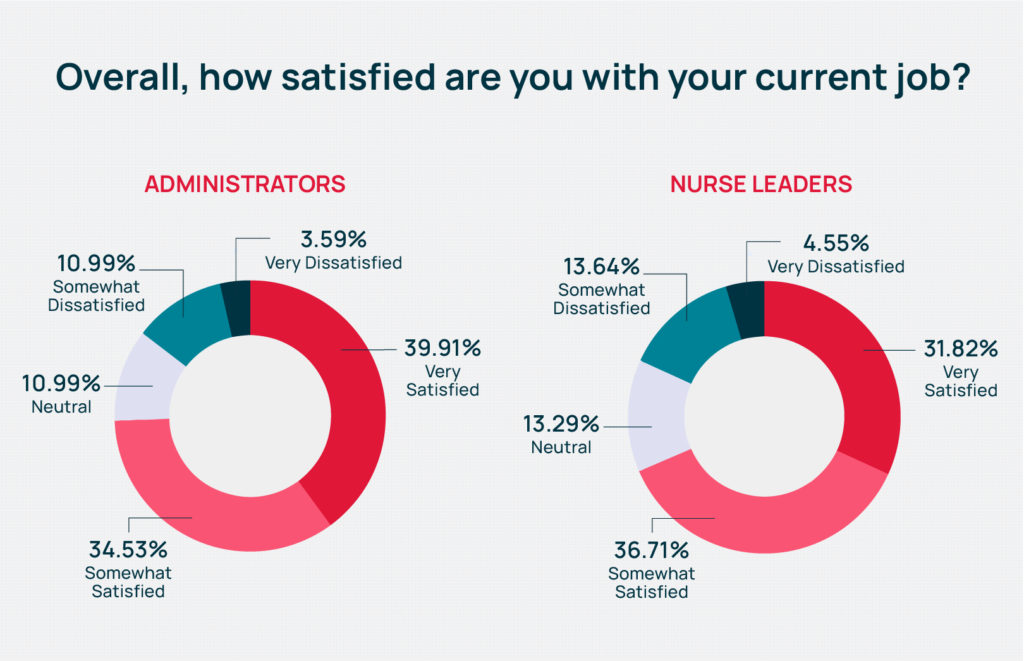

Just below 40% of administrators reported being “very” satisfied with their jobs, higher than the 32% among nurses. Overall, 71% of respondents said they were somewhat or very satisfied with their jobs in 2022, down from 74% in 2021.

Experts said that could be because many of them are not working at the full scope of their licenses, and they don’t get to devote much time to things they enjoy most about their work.

“Satisfaction is surveyed as (relatively) high, yet half the people surveyed pondered leaving their jobs in the last three months,” Silletto said. “The people we talk to are hitting their breaking points. There’s too much sacrifice, and their support systems are crumbling underneath them.”

Salary and workload blamed

Other Mood of the Market results indicate the numbers could be skewing lower due to salary and workload concerns.

Only 14% of nurse leaders said they were “very well paid” for the work they do. Among administrators, that share rose to 23%. Across both job categories, the portion claiming to be “very well” or “somewhat well paid” fell nearly 5 percentage points this year to 53.6%, from 58.2% in 2021.

“That is a little bit lower than I would have thought just because so many people are giving across-the-board increases and market adjustments,” said Matt Leach, a compensation associate at Total Compensation Solutions. “Right now, the environment is, if you’re an administrator or a nurse, especially a nurse, if you feel like you’re underpaid, you can definitely get more money going somewhere else.”

That kind of thinking may drive the number of nurse leaders and administrators seriously considering quitting. But so, too, may the crushing workload of the pandemic; continued regulatory, infection control and PPE-related challenges; and a workforce shortage that has left facilities nationwide looking to fill some 223,700 openings.

Nearly two-thirds of nurse leaders told McKnight’s they were asked to do too much at work “generally” or “very much.” The 64% combined rating beats last year’s 63%. It’s also a full 10% higher than the share of administrators reporting they’re asked to do too much in 2022.

Overall, slightly more than 58% of respondents said they were asked to do too much, with 35% saying generally they were not, and just 7% saying they didn’t think that “at all.” In 2021, just under 56% said they were asked to do much.

Too much hiring

In addition to filling multiple roles within the same building or overseeing more than one building while a new leader is hired, many are often seeing one routine part of their job explode.

“The volume of employee turnover means that all of these administrators and DONs who are considered hiring managers, the recruiting portion of their current job has to take up way more time sourcing, interviewing, selecting, onboarding, training, mentoring all these new people,” Silletto said. “How do we expect these leaders to sustain that additional workload that is not going away?”

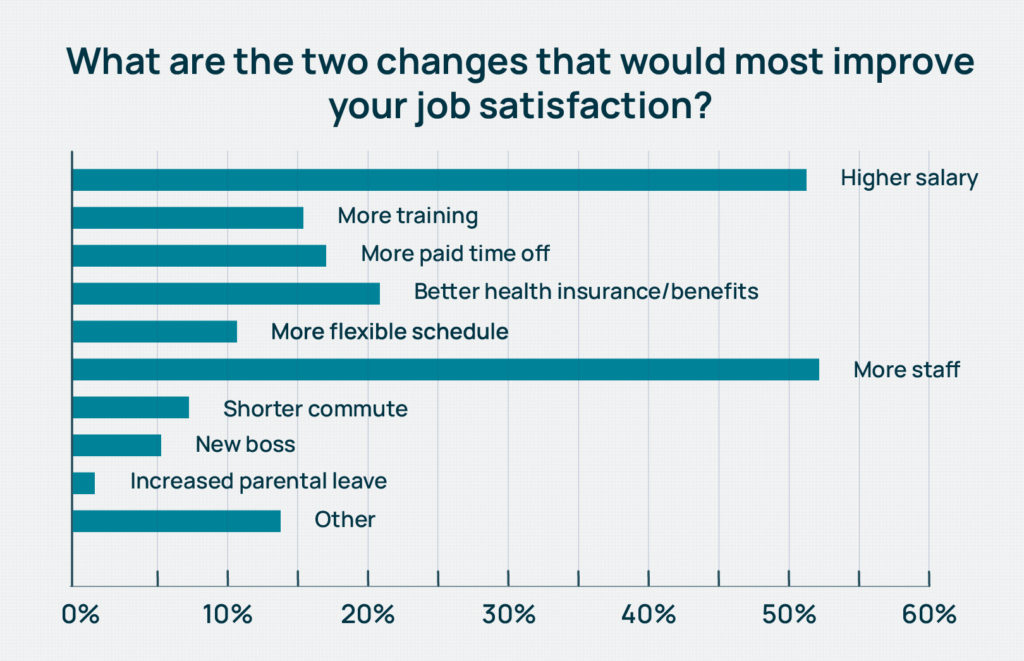

Leaders clearly want additional help. “More staff” edged out “higher salary” as the No. 1 way to increase job satisfaction, with 52% of survey-takers saying they would choose more staff as one of two biggest satisfaction drivers. That was down significantly from 2021’s 59%. The second-place 2022 choice was higher salary at 51% of respondents — a nearly 10-point jump since the 2021 survey.

When broken out by category, more nurse leaders chose higher salary (53%) to more staff (52%); the preference was flipped among administrators, who chose more staff most often (52%) and higher salary second most (50%).

“We’re seeing nursing homes give raises, market adjustments pretty much across the board but even with those higher salaries, they still cannot fill all of their positions,” said Leach. “I don’t think there’s an end in sight. Employees see that, and that’s the biggest issue.”

Big ‘Walk-Out’ projected

Most workers told McKnight’s they have “some” or “a lot” of latitude at work (90%), are valued by their colleagues (82%) and have good or excellent opportunities to advance their careers (56%).

But COVID continues to wreak havoc on staying power: More than 43% said the pandemic has made them more likely to leave their profession.

Following the mass exodus of the Great Resignation, Silletto is forecasting the “Great Management Walk-Out” as more leaders tire of “new normal” workloads. Despite mounting evidence of frustration among leaders, Silletto said she still hears about providers delaying advertising — or choosing not to hire at all — when people in positions without regulatory implications quit.

Silletto said many are frustrated by corporate decisions, sometimes made by higher-ups who have been out of the field for years and don’t understand increased patient complexity or ongoing pandemic pressures. Organizational leaders need to take demands for more staff seriously, she added.

“If they are telling you that they need more staff, it’s not just to fill the open positions,” she said. “Are you by chance, or have you in the last five years, not replaced people who left? Have you asked any of your leaders to just absorb more responsibilities when people have walked away?”

She pointed to the disappearing roles of assistant DONs and assistant administrators and recommended restoring them in larger buildings, or adding retention specialists or hiring support.

Seeking satisfying solutions

Signature HealthCare has kept its assistant DONs at all buildings, in addition to trainers and other unit heads who serve nurse leader roles. Chief Nursing Officer Barbara Revelette told McKnight’s earlier in August that the company will be focusing on recruiting and retaining more DON and related staff over the next 12 months.

It includes a DON council that will convene in-person meetings and try to address areas where managers feel squeezed.

“It’s listening. It’s being with them. I need to see how they’re trained, what their competencies are, to be able to truly develop and retain and also provide the best quality of care to our residents,” Revelette said.

Indeed, training factored into job satisfaction for DONs in the McKnight’s survey. After salary and staffing, rounding out the top choices were better health insurance or benefits; more training or learning opportunities; and more paid time off.

Matt Stokes, a compensation analyst with Total Compensation Solutions, said it was important to consider the age and market of employee groups when trying to assess the meaning of falling interest in benefits. Just over 25% of nurses asked for better insurance or other benefits this year; last year that figure was close to 27%.

“When you’re talking from the nurse’s point of view … it’s just gotten so expensive to live where they really need that cash in hand as soon as they can get it, and they’re willing to forgo anything in benefits, retirement just to get more cash upfront so they can afford their monthly bills,” he said.

Among administrators, the top five wants were rounded out by better health insurance or benefits; more paid time off; and a more flexible schedule.

Nearly 15% of all respondents wrote in other responses, including being able to “use the PTO I have” and “take time away from work” and “not being on call EVER AGAIN.”

Operating pressures, too

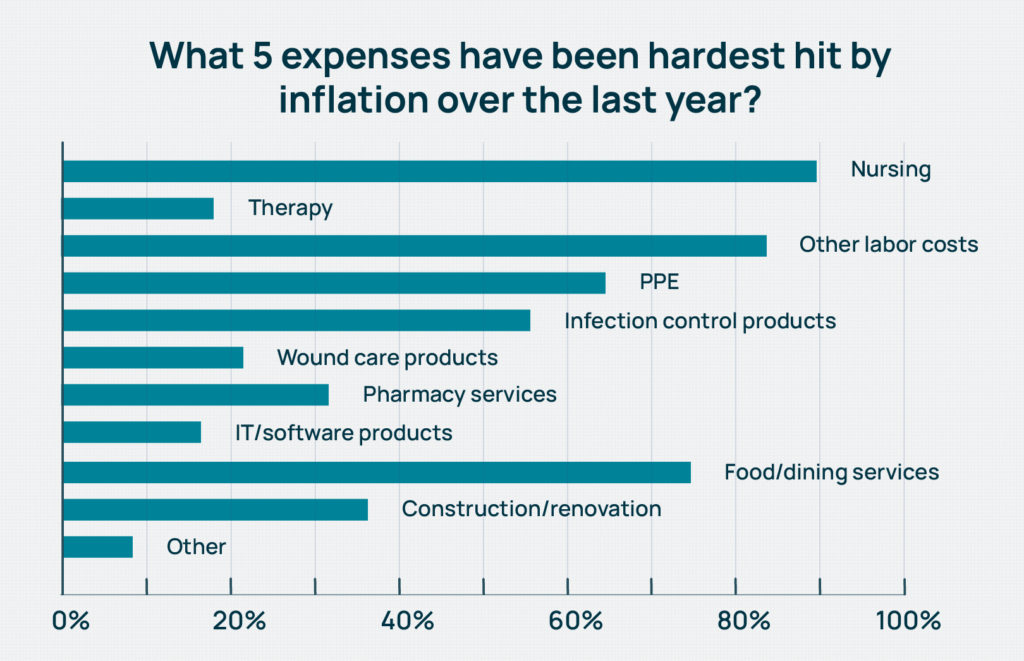

In addition to all the other pressures, building leaders are scrambling to cope with inflation and costs that have driven up the price of everything from personal protective equipment to pharmacy services.

With fewer job candidates, high demand and persistent pandemic conditions, it’s no surprise that building leaders put nurse staffing costs first. Nursing home nurses averaged double-digit pay increases this year, with hourly rates for certified nurse aides soaring by 11.2% to $16.87. Registered nurses reported a jump of 11.1%, according to the 45th annual HCS Nursing Home Salary & Benefits Report issued in late July.

But rising construction costs also were a strong contender, with about 36% of all respondents citing it among the costs most affected by inflation. The number rose to over 40% among the administrators-only crowd.

“We know of projects that were priced six months ago with certain financial models and now the project costs are 50% to 80% higher,” Lisa McCracken, research director for investment firm Ziegler, told McKnight’s. “It has been difficult to estimate costs with the needle constantly moving.”

Just under 50% of respondents said they’d put off a building or capital improvement project, while that portion climbed to more than 53% among administrators. Nurse leaders chose restricted admissions as a cost-saving measure (second most often at 40%), about 1.5 points higher than administrators. Twenty-nine percent in each job category said they’d discontinued services such as recreation activities, trips or entertainment.

Limiting investment in physical plant while also limiting admissions sets a dangerous precedent for skilled nursing operators, whether or not it’s due to costs of staffing shortages, McCracken said.

“There may have been providers who were going to embark upon reinvestment projects going into the pandemic, put those on hold and are now putting them on hold again because of cost escalation,” she said. “In those instances, you are now years behind a reinvestment that is needed to remain competitive and aligned with what the customer wants.”

6% more say census is back

McCracken said that overdue projects also are affected by lower census, which leads to reduced revenue.

Overall, almost 27% of all Mood of the Market respondents said that their census had already returned to pre-pandemic levels. Last year at this time, only 21% of survey-takers were there.

But for the rest, when more beds will be filled is scattershot. Fifteen percent predicted either the third or fourth quarter of this year, while about 19% chose the first half of 2023. Another 27% predicted full recovery in the second half of 2023, in 2024 or 2025. And just over 12% said they “never” expected a return to pre-pandemic levels, up from 9% last year.

“Reduced occupancy leads to financial challenges, which further pressures the ability to reinvest, and that is where the downward cycle comes into play,” McCracken noted. “We understand that these can be difficult decisions on the cost front, but we would encourage providers to explore all possible scenarios before pulling the plug on a project. Downsizing or a multi-phased approach might be the more balanced alternative, given all of the considerations at hand.”

From the September 2022 Issue of McKnight's Long-Term Care News