Flexibility, already a major buzz word in the skilled nursing sector, is becoming an even more critical tool for hiring managers and building leaders in 2023, results of the latest McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey show.

Following years of COVID conditions that have often called on staff to work back-to-back shifts and take on overtime they didn’t necessarily want, more nursing home employees are insisting on flexible scheduling. Respondents also indicated that not being able to offer flexible work is a major hiring and retention potential stumbling block in a new economy shaped by the rise of the gig worker.

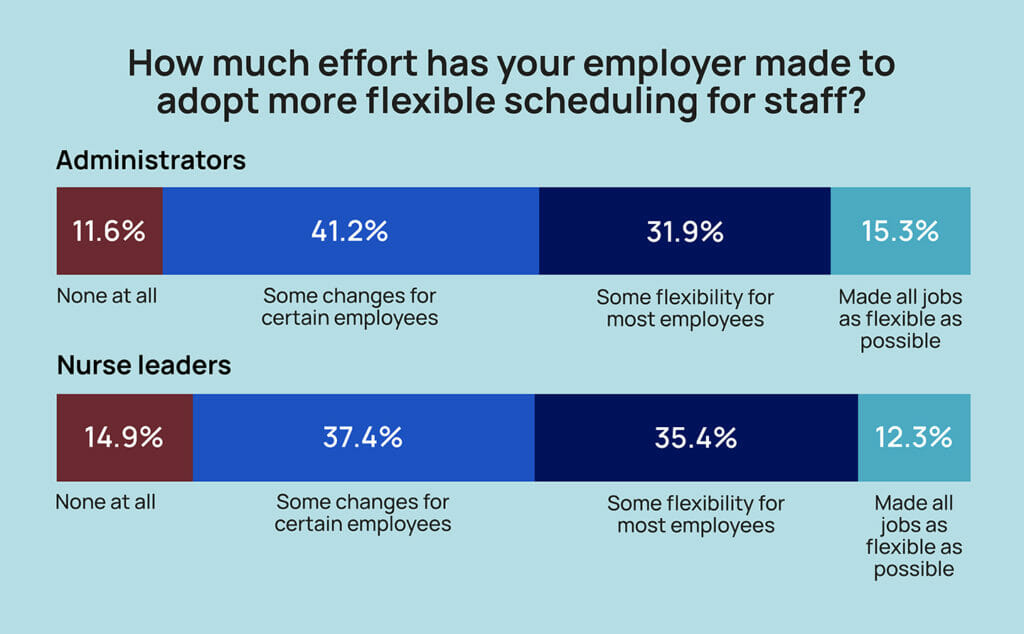

Overall, 40% of respondents told McKnight’s Long-Term Care News that their workplace had made “some changes, but only for certain employees.” Another 35% said “some flexibility is now available for most employees.”

While that represents three-fourths (75%) of respondents, some 13% said their facility or chain had made no effort “at all” to adopt more flexible scheduling.

“While accommodating flexible schedules can sometimes be a challenge for centers, providers need to change the way they have always done things,” said Kendra Nicastro, director of business development for healthcare recruitment firm LeaderStat. “If you are not adapting and developing new ways to attract candidates — flexible schedules, same or next day pay options, etc. — you will continue to fall behind and recruitment and retention will continue to be a challenge.”

The 2023 survey drew more than 500 responses from directors of nursing and their assistants, and administrators and their assistants. They sent mixed signals about the meaningfulness of their work, their willingness to remain on the job and the changes today’s employers need to adopt to keep them.

Flexibility takes all shapes

This was the first year the McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey specifically asked whether employers were offering flexible scheduling.

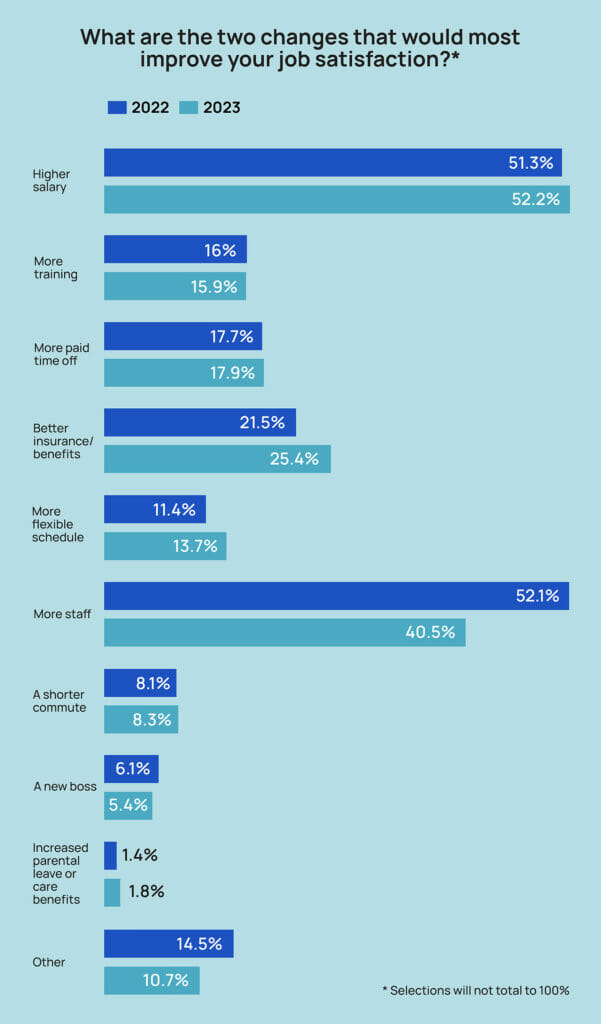

But in a separate question about potential changes that would most improve their job satisfaction, slightly more employees chose the option of a more flexible schedule in 2023 than in 2022, rising to 13.7% from 11.4%. Administrators were more likely than nurse leaders to choose the flexibility option at 14.6% vs. 12.3%.

But those numbers are likely far lower than if the survey had been offered to all nursing home staff, explained recruitment and retention specialist Cara Silletto.

“DONs and administrators have the most flexibility in the whole building. They can come and go whenever they want and if their kindergartener kid or grandkid has a 2 o’clock play, they can leave the building and go when most of their staff cannot,” said Silletto, president and chief retention officer of Magnet Culture. “So you’re not going to get flexibility as a top priority for top leaders because they are in charge of their own schedule.”

That said, their buildings’ operations are directly impacted by approaches that try to meet the desire for flexibility among other workers. Just under a quarter (24%) of survey respondents said their facility offered self-scheduling tools for employees; 46%, meanwhile, said their facility had increased part-time opportunities; and 29% worked at locations that offer three- or four-day workweeks.

Notably, 161 of the 500-plus respondents also filled in “other” options that showed, for the most part, a willingness by skilled nursing operators to explore flexibility. Those desired options included the use of 12-hour shifts; PRN schedules (sometimes through an internal float pool); staggered shifts to accommodate school start times and other personal needs; and shift sharing.

Several respondents also noted in terse terms that their owner or corporate leadership refused to be more flexible with scheduling, or that union contracts prevented facilities from offering some options peers at other locales had found success with.

“The more forward-thinking organizations are utilizing more flexibility strategies. But most companies, honestly, haven’t had the bandwidth to explore more flexibility options. The way they’ve always scheduled, they know it’s not working, and yet, they don’t know what else to do. They don’t know what else to try,” Silletto said. “I think some of them still dig their heels in, and I’m not sure how they’re still operating, to be perfectly honest with you. I think they’re using a lot of agency. And that’s what’s funny too, is there they have the flexibility. They’re just using agency for it.”

Katie Piperata said the leadership candidates she works with are “very much” demanding some flexibility, even if it’s just one day a week at home to catch up on all reports, emails and other non-clinical requirements. But she doesn’t see her clients, meaning nursing home HR leaders, budging much.

“When you’re leading the whole building either on the clinical or ops side, it’s the customer who wants to see you, it’s the customer who is wanting that visibility and that representation. So I get where the client is coming from on that,” said Piperata, workforce architect at recruiting firm MedBest. “But I also get that we’re in this gig worker mentality. People want the flexibility to be able to have a day to get everything done or to work for longer days because staff nurses are able to do Baylor [12-hour weekend] shifts and things that do allow flexibility. So I think we’re just seeing the DON and administrator saying, ‘I want that too.’ ”

Flexibility has limits

Ted LeNeave, CEO and founder of Accura Healthcare, operates 34 skilled nursing facilities in the Midwest. While he’s hearing more requests for flexible and remote work options, he sees some positions for which that’s just not aligned with the business of doing healthcare. For instance, he recently determined a DON asking to work four days a week in the building wasn’t a “good culture fit.”

“It’s not that kind of job,” he said. “We can have flexibility in other areas, but we can’t have flexibility to not be in the facility if your job is in the facility taking care of those people.”

Anthony Scarpino, vice president of talent acquisition for National Health Care Associates in the Northeast, takes a different view. He sees trying to be more amenable to employee desires as one way to avoid costly attrition.

“We don’t see as many people leaving the industry as we see people changing roles for additional pay, a better shift, more flexibility, a better commute,” he said. “I think the whole industry, not just senior living but healthcare in general, is really struggling with this idea of flexibility, particularly with so much attention being given to work from home outside of the industry. … There’s no silver bullet out there.”

He’s exploring adding self-scheduling technology, seeing that as one of the best possible solutions for the company’s leaders as they grapple with the issues. In the meantime, he’s trying to manage job candidates — from leaders to brand new CNAs — who ask for arrangements such as 12-hour shifts.

“We just try to be flexible with them as far as we can within the confines of our operation,” he said. “Whether it’s a 16-hour shift, no weekends, only weekends, days, nights, evenings, those different things. There’s all kinds of different scenarios that we try to piece together to accommodate.”

He’s also open to shorter shifts, especially as an alternative to hiring someone new or turning to agency to fill in-demand slots.

Seeking middle ground

Silletto is encouraging hiring managers to think of their staffs more as members of separate pods; one might be PRN, one might be part-timers; and another could be full-time, traditional eight-hour shift workers who never ask for accommodations. The employer can then work out agreements and pay incentives with each pod to ensure round-the-clock coverage.

“I would say an overarching theme — and employers hate to hear this, but it is a current problem — is fewer people in the workforce want to be told where to be when,” she said. “Offering as much flexibility and as many shift options and start and end times as possible helps it fit into their lives. A lot of people are less tolerant today of sacrificing for work.”

For leaders resistant to demands for flexibility, Piperata suggests testing it first in buildings where there might be less risk.

“If you have a 5-star building that’s performing well and the administrator and DON have been there a while, there hasn’t been a lot of turnover, why not allow something like that?” she asked. “It’s not in a regulatory crisis … I think that maybe they could start to look at it more from a custom standpoint. If your building is doing well, then you can earn this. If these two or three things are met, then this is something that we would work with you on versus just saying, across the board, ‘We’re not doing that.’”

Without more change, recruiting nurses who can find the hours they want in hospitals and keeping entry-level employees who have plenty of options in retail or hospitality will continue to be a slog, Piperata said.

Reluctant providers need to think about how their stance will position them in what will only become a more competitive landscape in the coming years, Nicastro added.

“When candidates see flexible scheduling in a job description,” she said, “they can assume that your building is proactively addressing employee requests for work/life balance and working to stem burnout.”

This is the second in a four-part series revealing the findings of the 2023 McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey. The first appeared Aug. 31. Check back Friday, Sept. 8 for the third installment on workers’ future plans.