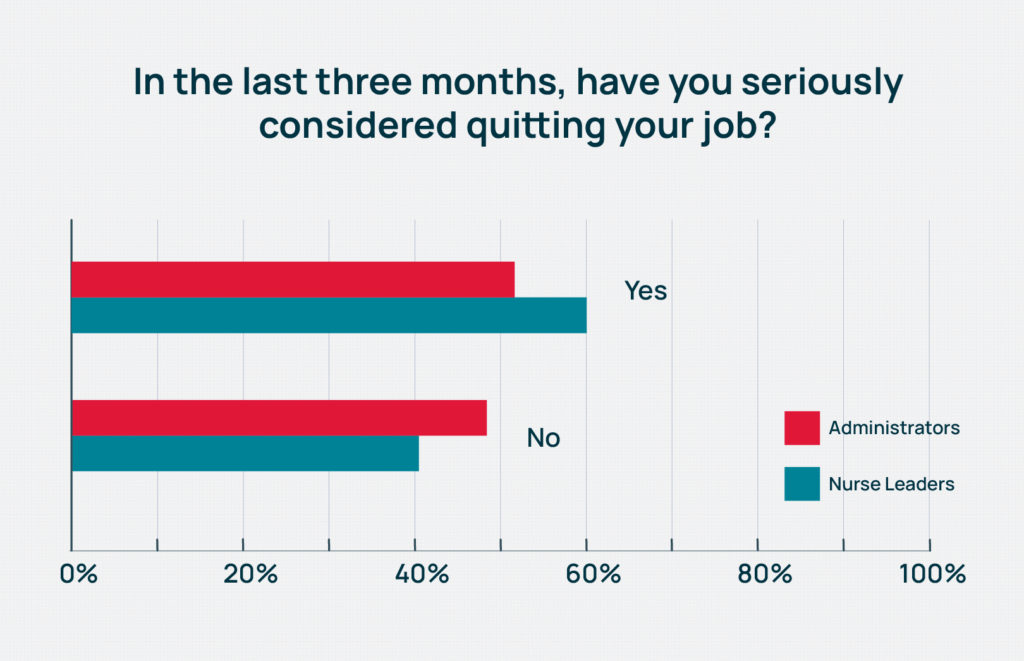

Nearly 60% of long-term care nurse leaders have seriously considered quitting their jobs in the last three months, a nearly 10-point jump since 2021, according to the fourth annual McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey.

That was trailed slightly by administrators at 52%, further proof that the turnover threat at the highest in-building levels is all too real. The 2022 findings come as regulators are putting more emphasis on staffing consistency.

The 2022 Mood of the Market survey drew nearly 750 responses from directors of nursing, assistant directors of nursing and administrators, who sent mixed signals about job satisfaction and their willingness to remain in leadership positions at the nursing home level.

Data was collected through email solicitations over a two-week period spanning late July and early August.

Cara Silletto, president and chief retention officer at HR consulting firm Magnet Culture, said she was surprised the findings weren’t more negative after 2½ years of nearly impossible working conditions. But she cautioned that the busiest, and maybe most dissatisfied, workers might have sat out this year’s survey. Anecdotally, she said, she hears there is no time out in the field “for anything that is not resident-specific or compliance-specific.”

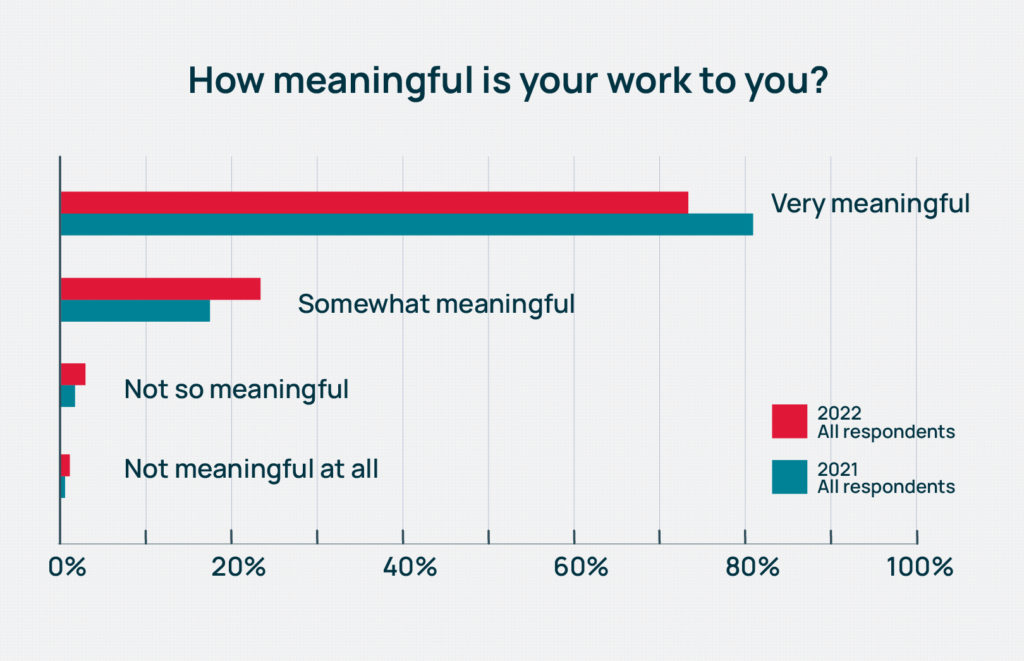

Among the most positive aspects of the survey remains the meaningful nature of the work. This year, 73% of respondents said they found their work “very meaningful.” Still, that’s a significant slide from 81% just last year.

“In general, DONs and administrators really like what they do. They really do love serving the residents, running the building and the mission of what they do. They don’t want to quit,” Silletto said. “But what I’m picking up on is that organizations continue to push these leaders beyond their limits and beyond what is sustainable long-term. That is a huge wake-up call that these organizations need to realize.”

Those thoughts were echoed by geriatrician, nursing home physician and Regenstrief Institute research scientist Kathleen Unroe, MD. She recently authored an editorial in The Journal of the American Geriatrics Society noting the negative effects of turnover at the administrator level, most notably when it comes to efforts to improve resident care.

While Unroe’s editorial noted that good administrators often leave for promotions, any turnover creates a void that may be disruptive, prompt other staff to leave, and require process reorganization under a new leader.

“The administrative team, their leadership sets the tone, creates the culture,” she told McKnight’s last week. “Their level of experience, their investment in the building is so evident when it is present. You can have all kinds of innovative, quality type programs under way, and when you have turnover in the clinical and administrative leadership, they have different priorities.”

Too much sacrifice?

Consistency may be a key goal for nursing homes, but this year’s survey indicates skilled nursing hasn’t staunched the kinds of wounds that lead workers to quit.

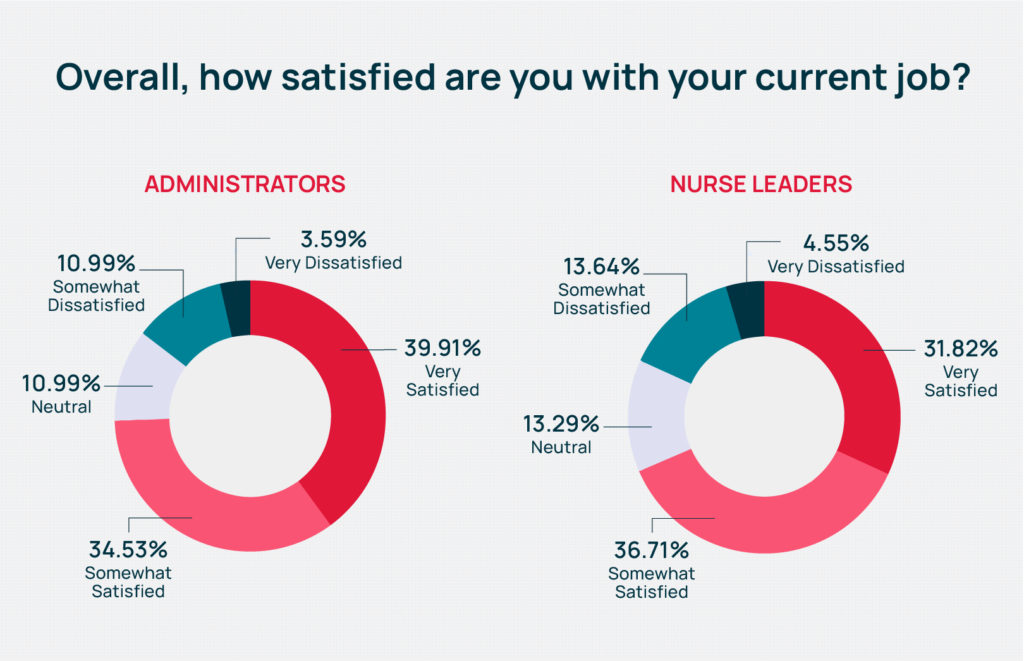

Just below 40% of administrators reported being “very” satisfied with their jobs, higher than the 32% among nurses. Overall, 71% of respondents said they were somewhat or very satisfied with their current jobs in 2022, down from 74% in 2021.

Experts said that could be because many of them are not working at the full scope of their licenses or positions, and don’t get to devote much time to things they enjoy most about their work.

“Satisfaction is surveyed as (relatively) high, yet half the people surveyed pondered leavinging their jobs in the last three months,” Silletto said. “The people we talk to are hitting their breaking points. There’s too much sacrifice, and their support systems are crumbling underneath them.”

Unroe shared stories of colleagues in nursing homes driving residents to medical appointments and filling in in the kitchen on a regular basis. Higher-level tasks like team-building and clinical goal setting may fall to the wayside when there are barely enough people to cover the basics.

“I wonder about that: how effective and impactful people feel like they are. There are a lot of day-to-day stressors, pressures and that may affect seriously considering quitting,” Unroe added.“They see meaning in providing care in this stage of life, and in the leadership position, they find meaning in supporting staff who are delivering that care. But the stress and whether you’re going to stay in it is, I think, more about organizational and system level factors: our survey and regulatory systems and the ability to retain the frontline staff so that you can invest in them.”

Salary and workload cited

Other results indicate those numbers could be skewing lower due to both salary concerns and overwork.

Only 14% of nurse leaders said they were “very well paid” for the work they do. Among administrators, that share rose to 23%. Across both employee types, the portion claiming to be “very well” or “somewhat well paid” fell nearly 5 percentage points this year to 53.6%, from 58.2% in 2021.

“That is a little bit lower than I would have thought just because so many people are giving across-the-board increases and market adjustments,” said Matt Leach, a compensation associate at Total Compensation Solutions. “Right now, the environment is if you’re an administrator or a nurse, especially a nurse, if you feel like you’re underpaid, you can definitely get more money going somewhere else.”

That kind of thinking may drive the number of nurse leaders and administrators seriously considering quitting.

But so, too, may the crushing workload of the pandemic; continued regulatory, infection control and PPE-related challenges; and a workforce shortage that has left facilities nationwide looking to fill some 223,700 openings.

Nearly two-thirds of nurse leaders told McKnight’s they were asked to do too much at work “generally” or “very much.” The 64% combined rating beats last year’s still-substantial 63%. It’s also a full 10% higher than the share of administrators reporting they’re asked to do too much in 2022.

Overall, just more than 58% of respondents said they were asked to do too much, with 35% saying generally they were not, and just 7% saying they didn’t think that “at all.” In 2021, just under 56% said they were asked to do much.

In addition to filling multiple roles within the same building or overseeing more than one building while a new leader is hired, many are often seeing one routine part of their job explode.

“The volume of employee turnover means that all of these administrators and DONs who are considered hiring managers, the recruiting portion of their current job has to take up way more time of sourcing, interviewing, selecting, onboarding, training, mentoring all these new people,” Stiletto said.

She has worked with communities reporting they are hiring as many as four times as many employees per month to keep up with turnover. Building staffing levels are so lean — many having eliminated their assistant DON roles years ago — there is no cushion. Once employees are in, they will likely have more questions, need more training and mentoring, and all of those factors have a multiplying effect on nurse leaders and administrators, Silletto noted.

“Where’s that time supposed to come from? I still have to do everything else that was part of my job, and if the company hasn’t offloaded some of those recruiting efforts and requirements … how do we expect these leaders to sustain that additional workload that is not going away?” she asked.

This article is the first in a Mood of the Market series. Read Part II in Wednesday’s McKnight’s Daily Update.