Skilled nursing’s employee turnover problem — long linked to issues with quality of care — is much worse than previously reported, according to a massive analysis published Monday.

Median turnover among nursing staff, factoring in data from virtually all U.S. nursing homes, was 94% in 2017 and 2018. More alarmingly, mean turnover rates hit 140.7% among registered nurses, 129.1% among certified nursing aides and 114.1% among licensed practical nurses. Researchers used a method that weighed the amount of direct care nurses provided to residents.

The calculations appear in a Health Affairs study written by researchers from the University of California Los Angeles and Harvard Medical School. Using employee-level Payroll-Based Journal data, they found wide swings in turnover depending on state or quality indicators, such as overall star ratings, overall staffing levels and health inspections.

The researchers called for staff turnover rates to be publicly reported as a way to leverage better wages and benefits from employers, and generate more funding from states.

While it probably wasn’t unforeseen that 1-star rated facilities would have the highest median turnover among all nursing staff at 135.5%, some things were.

“Two things really surprised me,” said lead author Ashvin Gandhi, Ph.D., assistant professor at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. “One is that we measure rates that are higher than the majority of (past) studies. Two is that these rates are fairly persistent across the country.”

Previous studies — limited by lack of data, self-selecting surveys and small sample sizes — found wide turnover variations. The largest, however, cited averages of 78.1% among CNAs, 56.2% among RNs and 53.6% among LPNs.

In this study, researchers had access to daily staffing hours from 15,645 nursing homes and could examine the amount of direct care employees delivered in the last three months before their separation. The percentage of turnover represents the percentage of care that “turns over” when an employee leaves.

Turnover correlates with other negatives

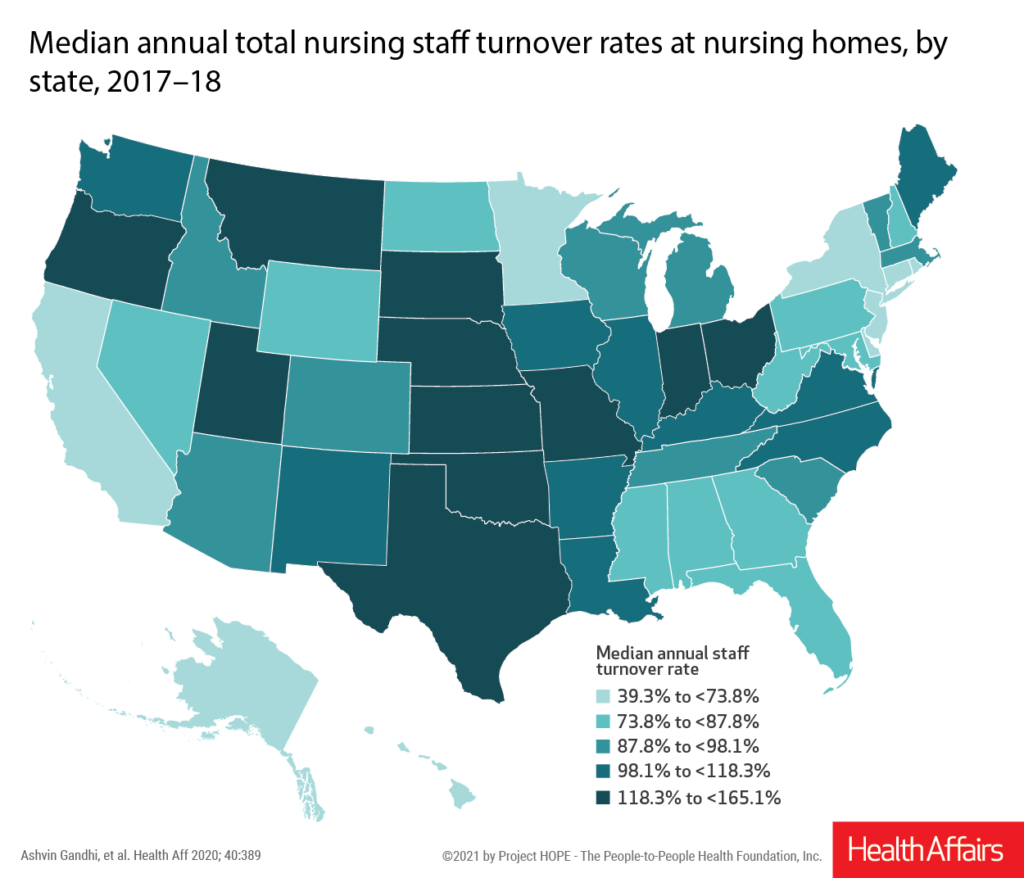

Gandhi and co-author David Grabowski, Ph.D., professor of healthcare policy at Harvard, found that even states with the lowest median rates were in the 39.3% to 73.7% range when all nurse types were taken together. Hawaii fared best at 39.3%, while Oklahoma was worst at 165.1%. Facilities in urban and poor areas also saw consistently higher turnover.

But rates were also tied fairly uniformly to key features beyond location.

“There’s a very clear negative relationship between quality ratings and turnover,” Gandhi told McKnight’s Long-Term Care News. “Higher-rated facilities tend to have lower turnover rates. … Lower-quality facilities may induce staff to separate more frequently. They may choose to leave facilities that are low quality specifically for the reasons that make them low-quality.”

The same negative relationship between turnover and quality applied to the star ratings for health inspections, quality measures, overall staffing and RN staffing, the study proved. Total nursing staff turnover rates also were higher at facilities that were for-profit, chain-owned or predominantly Medicaid funded.

Gandhi and Grabowski suggested states could reduce turnover through higher Medicaid reimbursement and incentive payments, particularly targeted increases that reward retention.

“Posting these data makes this measure of a facility’s staffing quality much more salient for consumers, and thereby may put pressure on facilities to try to increase retention,” Gandhi said. “The publication of these data on Nursing Home Compare will make it easier for regulators and academics to further investigate what the implications of the industry’s high turnover rate are for patients, as well as to investigate what policies are likely to reduce this sort of alarmingly high data.”

Tie Medicaid increases to staff wages

Lori Porter, co-founder and CEO of the National Association of Health Care Assistants, said the findings validate the turnover issues her organization sees every day.

“NAHCA has always believed that CNA turnover data should be included in the Nursing Home Compare metrics so that families, residents and potential employees can make informed decisions,” she told McKnight’s. “If turnover data was included as a metric on Nursing Home Compare, turnover would become a greater priority for employers and regulators.”

George Linial, president and CEO of LeadingAge Texas, argued that factors out of providers’ hands, such as local poverty rates and depressed wages, might make a public rating unappealing. But in a state where daily Medicaid rates hover near $150, his organization fully supports the idea of using such data to pressure state funders.

“We really want any increase in Medicaid rates to be tied to staff wages and benefits,” Linial said. “We definitely know that we need more funding, but there has to be accountability for that.”

In Texas, the Nursing Facility Direct Care Staff Rate Enrichment was created to pay providers more for improved staffing hours, but Linial said it is routinely underfunded. Without the incentive payments, it is hard for providers to increase hours and wages.

Texas also cut funding for its own nurse staffing studies.

Gandhi said he expects the PBJ data to support more research on the implications of turnover on health outcomes and quality measures. He and Grabowski are already working on another paper examining the link between turnover and infection control violations.

But he said providers shouldn’t ignore the intangibles either.

“These are residential patients, and this is their community,” he said. Nurses “know your conditions, your wants, your needs, your personality. They may be able to make your experience, and make you happier in ways that are not usually measured by health outcomes. We probably shouldn’t lose sight of that.”