The plight of a private-equity backed, multi-state nursing home chain demonstrates the ugly challenges operators could face as officials ratchet up regulatory and transparency pressures and large-scale investors move out of the skilled nursing space.

Federal officials have announced they will terminate Medicare payments to Viviant Healthcare of Bristol, TN, on Sunday (Dec. 10). That comes on the heels of two Vivant facilities in South Carolina being moved to the Ensign Group, following a state-initiated receivership this summer.

In all, six Viviant facilities are majority-owned by the Goldner Family Trust and Samuel Goldner, according to a federal database. They’re part of a larger nursing home portfolio held by the trust. Nursinghomedatabase.com reports that the trust has at least a 5% ownership stake in 14 facilities in six states.

But many of those facilities appear to be hanging on by a thread financially.

Private equity critics see the apparent collapse of Goldner’s holdings as a harbinger for other facilities that find themselves in the hands of such owners, and by association, the nursing home sector in general.

A bank that helped finance operations at two other Viviant sites in Tennessee asked a federal court on Nov. 21 to appoint a receiver for both, calling the Goldner trust and its partners “insolvent on both a cash flow and a balance sheet basis, inasmuch as they are unable to pay their debts.” The related parties owe nearly $15.5 million in payments and interest alone, court records show.

Local media also has outlined a systemic failure to pay vendors and equip other Viviant facilities with supplies needed by staff and residents, a practice that Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services documents indicate went up the chain to owners.

The accusations echo ongoing concerns about the role of private equity owners in the skilled nursing space. They’ve been a repeat target for the Biden administration, whether in proposing its first-ever staffing mandate for nursing homes or increasing transparency requirements to paint a clearer picture of skilled nursing owners and their partners.

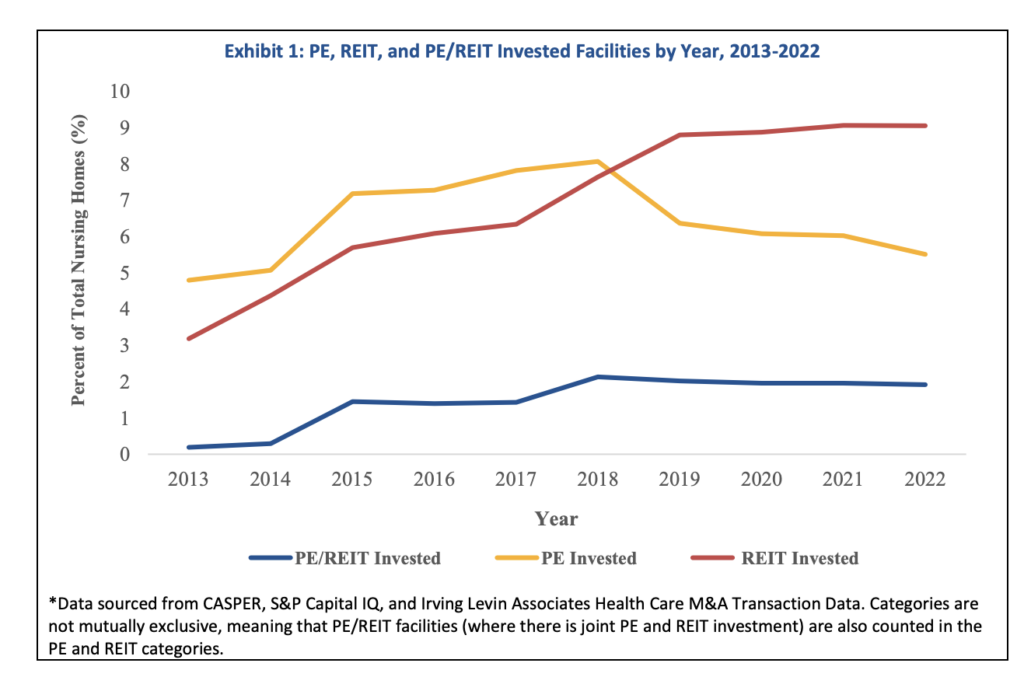

The latest transparency rule finalized in November establishes definitions of private equity and real estate investment trusts for reporting purposes. It included a research brief by the Health and Human Services Office of Behavioral Health, Disability and Aging Policy. Researchers found that private equity ownership in nursing homes had fallen to about 5% of all US facilities by 2022, down from 8% in 2018.

But as large-scale PE investors move out of the space, some observers predict smaller players may move into the void.

“I don’t think PE firms are nearly as interested in nursing as they were 10 years ago or 15 years,” said Eileen O’Grady, research and campaign director for healthcare at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project. “But I also think the type of PE firm that’s investing in nursing homes has shifted and will continue to shift.

“In the past, bigger name PE firms that had lots more money and did lots more things were the ones investing in nursing homes. But over the last few years, it’s shifted to these boutique private equity firms or family investment offices that I see as the bottom feeders of the PE world. They’re buying into an industry that other PE firms have decided is no longer going to make the kinds of returns that they’re aiming for.”

But those firms are no less focused on squeezing out generous returns on their investments; those efforts could just divert more cash away from frontline care and into related parties quickly, O’Grady warned.

Each negative PE story increases scrutiny of private owners in general, who argue they have been unfairly lumped in with a few unscrupulous investors.

“I’ve been publicly supportive of this,” Rick Matros, president and CEO of Sabra Health Care REIT, told McKnight’s after the latest rule was finalized last month. “There are groups that have opaque ownership structures so you don’t know who owns what. REITs have never taken steps to disguise/hide ownership.”

The American Health Care Association has called PE rhetoric and rules a distraction, repeatedly noting the low prevalence of private equity in the sector since Biden blasted Wall Street’s involvement in nursing homes during his 2022 State of the Union address.

Too little, too late?

O’Grady says some of the CMS efforts, while laudable, are coming too late. PE firms today are finding more traction in other healthcare sectors where they’re less regulated, be it home care or durable medical equipment.

But the practices replicated by PE firms over the last decade — such as real estate sales followed by lease backs, management fees, and the establishment of related parties to do business under the same corporate umbrella — are now widely practiced by all kinds of private owners.

“The table was set for private equity to come in and exploit a lot of loopholes that [CMS] is slowly trying to patch, but when you have all this money flowing through the system and little to no accountability from CMS and how it’s spent, this is the type of behavior you get,” said Sam Brooks, director of public policy for The National Consumer Voice for Quality Long Term Care, a consumer-oriented group that has been a major critic of investors in skilled nursing.

Brooks believes the HHS estimate and others that put PE ownership in the single digits are too low, simply because the current reporting doesn’t go high enough to reveal all layers of corporate structure. He says he often sees such buyers or lenders associated with PE firms at work in remote areas, but their borrowers aren’t necessarily reflected in publicly available records.

He supports new rules that might help reveal more PE ownership, as well as activity patterns of big, well-known players such as the New Jersey-based Portopiccolo Group. That firm is associated with at least 135 facilities, according to new ownership data from CMS.

Quality concerns

The involvement of Portopiccolo and other PE firms has become a natural curiosity for consumers as a growing body of research associates PE-backed facilities with lower quality and other negative metrics.

“Critics of PE acquisitions note that these firms typically have little experience in the provision of care and seek short-term profits over patient health interests,” the November HHS brief noted.

“Additional concerns include the potential for PE firms to prioritize short-stay, post-acute care patients over long-term residents, a group for whom federal reimbursements are significantly higher compared to state Medicaid reimbursements for nursing home care, researchers added. “These concerns are consistent with research [that] found increased short-term mortality, higher antipsychotic use, reduced patient mobility, lowered nurse hours per resident day, and increased costs for post-acute patients following PE acquisition.”

PE facilities had the lowest inspection,staffing and overall star ratings among six ownership types compared by HHS.

Goldner facilities had an average rating of 1.77 stars and 1,019 deficiencies for a total of $2,4 million in fines, according to nursinghomedatabase.com. Among the much larger Portopiccolo portfolio, a Consumer Voice analysis of CMS data found 15% of facilities have abuse icons; they average an overall star rating of 1.9; and have a quality measure rating of 2.6.

McKnights’ attempts to reach Goldner executives through their nursing homes or through a website for Goldner Capital Management were unsuccessful. Portopiccolo also did not respond to a request for comment.

Staffing pressures may slow interest

After purchases, PE facilities saw a 12% drop in their RN staffing compared to other for-profit facilities, according to HHS.

That’s a major way most PE firms, regardless of sector, increase their revenues, said O’Grady. She’s witnessed fast and steep cuts to staffing in hospitality and retail sectors when PE swept in there, often followed by bankruptcy filings or rapid-fire sales when the businesses can no longer stand up to the pressures.

Because most PE firms are limited partnership or limited liability companies, their losses are typically capped at whatever they’ve put into the business.

O’Grady’s not been surprised to see the same model repeat itself in long-term care settings.

She doesn’t see any of the CMS transparency rules to date keeping the PE firms still in nursing homes in check.

“I think that all of the sort of regulatory and political attention to nursing homes now is the result of behaviors PE firms were doing a while ago,” O’Grady said. “The regulatory and legislative response is just now catching up, and it’s sort of too late.”

Instead, market trends and staffing pressures could be the real difference-makers, argues Brooks.

“There’s a couple ways that I think you can drive out private equity: One is something similar to transparency, and that’s creating a direct care spending ratio where 80 or 90 cents out of every dollar goes to care,” he said. “But also we see a staffing standard as another way to do it. It’s an inadvertent direct space spending ratio. You need to spend enough money to get to this number. … That’s a very similar thing in some ways to a profit cap.”